The election of Barack Obama signaled the dawn of post-racism in America.

And yet here we are, sixteen years later, in the murky half-light of a sun that just can’t break through the clouds.

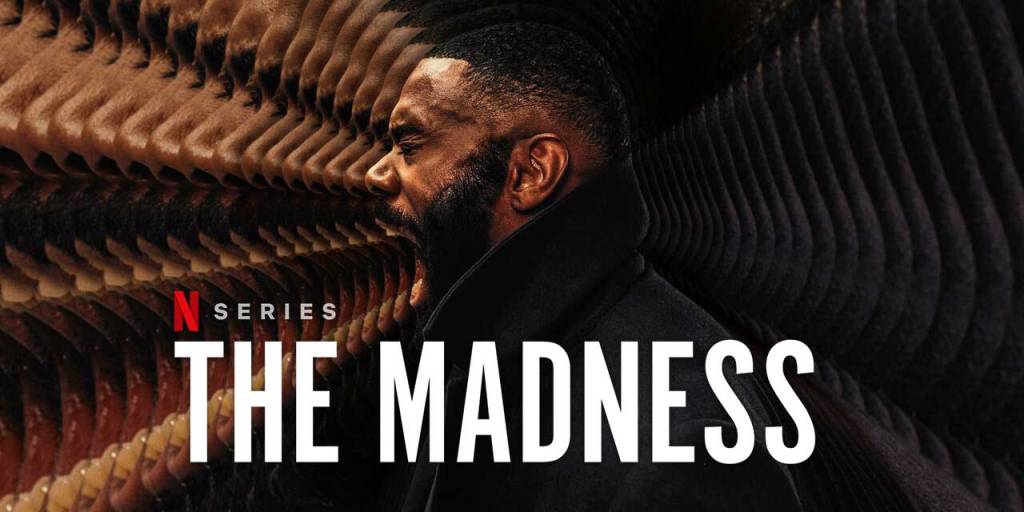

Series like The Madness, recently released on Netflix, reflect this atmosphere our nation finds itself in.

Woke enough to see stories of personal growth fighting alongside and against systemic racism.

Enlightened enough to document and criticize constructs that oppress and limit.

Yet realistic enough that Muncie Daniels’ living nightmare seems very much a possibility.

Growing up white in the last few decades of America, fictional TV did (and would) not offer the true experience of people of color. Eric Estrada offered a palatable Hispanic citizen as an officer of the law. Robert Guillaume spoke a perfect King’s English as he politely answered the door. Hollywood very much curated the vision of people of color. If we did see the struggle of their experience, we certainly didn’t blame ourselves for it.

We decided we wanted to have as many Black characters as possible in the show. Part of what I think we did in the show, and I think is really cool, is that this is a show anyone can watch and enjoy, and we are treating our Black characters, our primarily Black cast, like most shows treat white characters. They can just be people. They can be themselves because they’re not one of the two Black people in the show [and] have to represent all Black people. They can just be people.

VJ Boyd, co-showrunner The Madness in The Hollywood Reporter

In The Madness, Muncie Daniels’ struggle is very real. He must balance internal conflict with the outside forces that threaten to destroy him.

Muncie Daniels’ situation is amplified and magnified for dramatic effect, but the frustration and helplessness that he feels very early on – in conversation with Kwesi (even before he’s forced to drop his case) and especially in the interrogation room with Philadelphia police – are palpable. They are meant to be and feel outsized here because often the constructs racism has erected are unscalable. A person of color may not find himself at the center of a conspiracy master plot, but the exaggerated elicited emotions here serve to prove the effect in any situation where personal actions and the truth don’t necessarily enter into the equation.

The generational experience also weaves a meaningful thread through this story. Muncie is haunted by the ghost of his father’s actions. Isiah, while somewhat of a father figure, also reminds Muncie of his resemblance to his father’s flaws. Demetrius corrects his father on the terminology of his generation when Muncie tries to say D’s friend lives in the projects. And while Kallie is also Muncie’s offspring, she is just older than Demetrius to offer a sage outlook on his performance as a father and what his actions and attendance say about him. The many ages and stages of living in the racial state that each generation did are well represented and contrasted. The interactions between generations do well to represent the influence and evolution of experience.

It is refreshing to see a mainstream series accurately reflect what has survived the ‘post-racism’ movement of America. Unfortunately, there is always another Rodney Kraintz, as he himself posits to Muncie in the final scenes. There is always a larger, more powerful, and insidious construct pulling the strings behind the scenes.

Our nation has ticked the needle to a vibration just high enough to reflect the struggle and validate the experience – but not enough to dismantle the attitudes and oppression.

Great change always begins with the artistic vision and lens, but how do we, as individuals and a nation, change the unjust reality people of color face in our nation?

We can start by exposing the madness for what it is and not allowing it to activate the madness within us.

As always, any social commentary of racism and its wide-reaching effects made in this blog are made with full acknowledgment of the fact that they are through the lens of my whiteness.

Related: