“I sounded the lines out aloud, feeling the rhymes growing delicious on my tongue. Later I went to the Encyclopaedia Brittanica and looked up William Blake. I couldn’t believe it. He died nearly 170 years before me, but his words grew a thriving forest in my head. A thought, I understood it then, and its incendiary mind, could outlive itself. A well-made word could outspan carbon, and bone, and halved uranium. Until now, I imagined the world divided in two halves: the world of the spiritual, of my parents: Jah and levity, vibrations, energies, and chakras. And then, there was a world of things I could measure and understand, visible and knowable. Now, I felt there was another world just out of reach. A gossamer wing flashed against the bedroom window. I took out my journal and wrote my first lines of poetry in vines of cursive. Wings in the sunlight, wings against my dress. I pulled wing after luminous wing from my mouth. Watching them flutter alive with each word, my hands a vibrant garden. The poem was called ‘The Butterfly,’ the first to pull itself from the soft veil between all worlds, a seam to slip through to any place, any time. I knew then that as long as I had a word that leapt aflame in my mind, I would always be living in an age of wonder.”

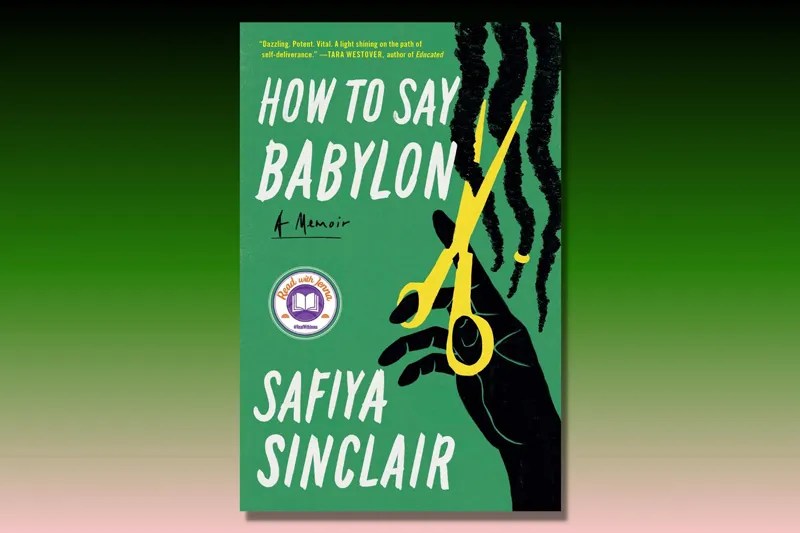

from How to Say Babylon: A Memoir by Safiya Sinclair