The other evening, as I lay in my seven year-old’s bed waiting for sleep – hers, though my own comatose mini-nap usually comes first – an unexpected thing happened.

No, it wasn’t my questioning whether I should still be or have ever even started lying with her before bed without: a. spoiling her, b. impeding her sleep progress, c. prolonging this nighttime ritual until we’re both old and gray. That’s been a constant since she first balked at sleep as an infant.

As they usually do, an important revelation snuck out in those twilight murmurs.

“When I grow up, I don’t want to have children.”

My heart instantly hurt for so many reasons.

Sadness for her, that she wouldn’t experience the wonder that is mothering. The fierce, warming, all-enveloping love that it is to raise a little human into a big one.

Regret for me, that I somehow portrayed motherhood to my children in a poor light. That I did them a disservice by not loving it enough or not showing them enough love.

But even as I type that, I can’t believe that I don’t show my children enough love. Surely, they know they are loved. Does my fault lie in my sometimes less-than-joyful servitude?

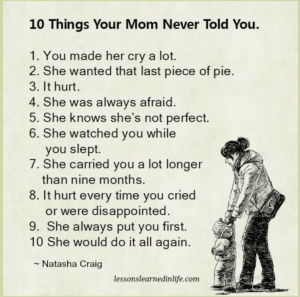

As beautiful a sentiment Mother Teresa of Calcutta shares about washing the dish because you love the person who will use it next, that doesn’t make me more likely to wash dishes or to do so without complaining. Perhaps you’ve seen the list of things your mother never told you.

While many of these ten things are true on some level, I cannot subscribe to this level of subterfuge. Sacrifice and selflessness certainly have their place in parenting, but to sacrifice to the extermination of self is something for which I cannot get on board. Perhaps that means I am not destined for sainthood, but I also believe God created each of us as a special, sacred self to be celebrated – not obliterated.

I also feel it is disingenuous to serve with a smile when anger and resentment broil below. Why can’t we be authentic with our partners and children about how hard this path is? How we serve with love, but also appreciate being appreciated and, even more, equal distribution and support.

By speaking truth about my struggles in motherhood, I hope my daughters will see the inequalities in expectation and systems of modern motherhood. I also hope they will realize the hard-earned worth of fighting for a connected, loved, valued family.

Because while I stand as a symbol of the greater mantle of motherhood for my children, I am also human.

I hope the toil I am totally transparent about will not dissuade my daughters from becoming mothers themselves, but make them realize there is no perfect ideal – except perhaps love.

I also hope that my seven year-old’s proclamation didn’t stem from Cookie World C’s unnecessarily medicalized version of a plastic horse giving birth she viewed earlier that day.

In any event, I have some work to do, but tomorrow’s another day . . .